It never ceases to amaze me how many D&D games ostensibly set in the Middle Ages are really set in a fantasy version of the American West in the 1880s. Most people don’t have a good grasp on medieval culture beyond knights and castles, so they imagine it was pretty much like the oldest thing they do know about: movies set in the Wild West.

Now, it should be said that everyone is entitled to do their adventuring in their own fantasy world, and it doesn’t have to mirror medieval England and France. But when people’s fantasy world sounds suspiciously like a cowboy movie, it starts to feel very silly. To be sure, if you want to play in an actual Old West setting, go right ahead. It would be an interesting campaign setting.

The lack of historical understanding shows in a lot of what people say and do. Towns and villages are often depicted as isolated, like Old West cow towns, when real medieval settlements were just a few miles apart. But there are many other errors that, corrected, can make your campaign better as well as more historical.

And don’t worry about a more historical campaign being too generic. Standard D&D-style settings are so ahistorical, that the more history you add, the more unusual it seems. Imagine a realm where the nobles speak a different language from the peasants; and there is a town crier who shouts the local news. That was medieval England for centuries after 1066.

Published adventures may talk about a “sheriff” of the town. Sheriff has always been a county position. (Old West towns hired a marshal, a detail even cowboy movies sometimes got wrong.) They often call people “farmers”, but that term didn’t exist until the modern era. President George Washington called himself a “planter”. His 8,000 acres at Mount Vernon was a pretty typical lordly domain–about five manors.

Literacy

A lot of campaigns latch onto the idea of “quest board” that looks a lot like a billboard (that is, a board for posting handbills) from the Old West, complete with wanted posters. There are even scale miniatures for them.

It should go without saying that such things didn’t exist in medieval Europe, because hardly anyone apart from nobles and clergy could read. Instead, they had town criers, and isn’t a town crier a more interesting way to get news?

Note the way these bills require the printing press and mechanical reproduction of engravings and assume not only general literacy but the existence of “detectives” and “lumberjacks”.

Social Classes

At the foundation of society in the Middle Ages were peasants, who made up ~90% of the populace. Peasants were serfs (field laborers attached to a manor) or freemen. Yeomen sat above peasants, because they possessed a bit of land of their own. Yeomen had larger, nicer homes and servants of their own. They held their land directly from the king, and so owed nothing to any other lord.

People who lived in towns and cities were freemen called burghers. Above commoners were:

- Knights (but knighthood was not inherited)

- Gentlemen and gentlewomen (often the children of lords and nobles but not possessing lands or titles; this is a good class for the player characters)

- Lords of the Manor (gentlemen who actually possessed land but no noble title)

- Nobles; mostly barons and earls in Britain but counts and dukes were brought in by the Norman French

- Royals, like princes and kings, who were usually sovereign (that is, they owed no fealty to a higher authority, altho in practice they often bowed to the Pope).

Most of Europe in the Middle Ages was kingdoms, but there were also two empires. In the Byzantine Empire, altho supposedly handed from successor to hand-picked successor, the imperial throne was largely occupied by whomever could garner support from the Senate, military, and common people. In the Holy Roman Empire, the emperor was elected by semi-sovereign noblemen; but thruout the High Middle Ages, no noble could gather enough support to take the imperial crown.

Empires tend to have a standing army with professional soldiers, as opposed to the temporary armies raised by feudal nobles.

Landlords Were Warlords

One important thing to remember is that virtually every male trained for war, and feudal obligations meant both rent and service. In wartime, this meant military service on campaign, but in peacetime, a knight might act as bodyguard and advisor for a few weeks–a great role-playing opportunity. Yeomen were required to practice archery. Burghers mostly trained as footmen. The gentry and nobility either trained as knights or joined the clergy. Nobles weren’t the effete aristocrats of later times–they were great warriors. They trained constantly for war by holding tournaments and going on extensive hunting trips where they camped in the forest and speared boars with lances. In a D&D world, they certainly would have gone monster-hunting.

The Manorial System

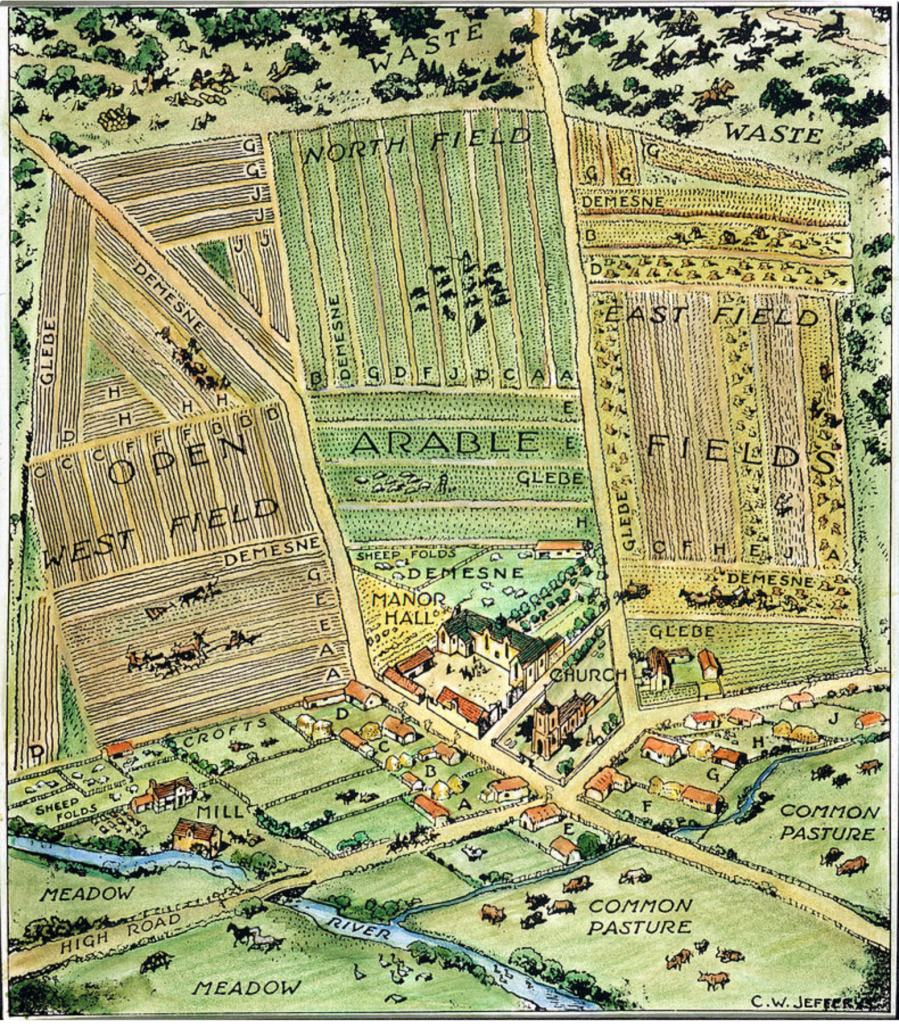

Essentially, every plot of land was part of some lord’s manor. Lords typically had several manors, each about 1000-2000 acres (two or three 1-mile hexes). Larger landholders were often given manors scattered hither and yon so that they didn’t hold a particular geographic area, which could lead to uprisings. But where there were a few manors clumped together, the lord would make his home. Each manor needed a manor house, often fortified, run by a bailiff. Nobles would have a castle run by a castellan. Knights would typically have just one manor (a knight’s fee or “fiefdom”).

Each manor had a village attached to it (called a “hamlet” if it was too small to warrant a church). The peasants lived in the village and worked in the fields and pastures under the supervision of a reeve, who was one of their own, elected by them. The village had no walls and was also home to a blacksmith, baker, and perhaps a miller or brewer. Many people (alewives) brewed ale at home; those who sold it to the public ran a “public house”. Beer (which contains hops, while ale does not) kept longer and so could be sold away from where it was made. A village typically had only one oven, owned by the lord.

If the manor was attacked, the villagers would run into the manor house.

A villager’s cottage was generally one room, with a central fire pit, with the smoke filtering thru the thatched roof. If you were wealthy enough to have more than one room, you probably brought your animals into the second room at night when it was cold; their body heat kept the house a little warmer.

Village Population

A village was about 50 to 150 people–just enough to tend the fields and livestock of the manor. The village had one church that could accommodate no more than about 200; likewise, the manor house could accommodate no more than that during an attack.

The lord of the manor was a member of the gentry or nobility. Everyone who lived on a lord’s land (including those in a town) owed him rent as well as support during a war. A lord would be expected to provide a certain number of archers, footmen, and perhaps set number of knights to his liege (usually the king but sometimes an earl). Knights–who could be of any social class–were obligated to serve 40 days a year, either in war or garrison duty (manning a castle) or retinue (traveling guards), as well as being available for councils to help advise in decision-making. Lords generally had a say in who married whom in a village, since it affected the number of people whom he could count as his subjects/workers.

In exchange, a lord provided security and protection from raiders and invaders, as well as traditional things like a certain amount of cloth each year for making clothing. In the event of attack, villagers would run to the safety of the manor house walls. Those who lived near a town or castle would flee there.

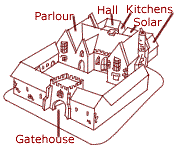

For the lowlier of lords, the manor house might be little more than a fortified stone house with a large hall and a few rooms for food (pantry and buttery) and a private parlor. The lord’s servants–and sometimes the lord and lady–slept together in the hall.

Towns & Cities

Towns grew up on major roads to provide a weekly market to locals. But only guild members could buy and sell, so all craftsmen and tradesmen (and their wives) were members. Shops in a town were workshops; there were no such things as stores and certainly no “general store” like in an Old West town. Stores weren’t invented until the 1800s.

In the Middle Ages, you bought things at the weekly market in the town square or commissioned them from a craftsman or tradesman. They made almost everything to order in a workshop, because they could only make one at a time.

Only very large cities had beggars or people who made their living by thievery; people didn’t slip thru the cracks in smaller cities and towns: administrators were obligated to know every man and be able to account for him. It was illegal to live without “visible means of support”. Even prostitutes were usually licensed.

The burghers who lived in the town still paid rent to the local lord (sometimes via the town administration), but in a chartered city, that lord was the king. So don’t think of towns like those in the Old West, being independent and isolated. Villages dotted the landscape every couple of miles, and towns were 15 to 20 miles apart. Only the rich could afford horses and carriages, so these places had to be within walking distance.

People also commonly get the community size wrong. A village was only 75 to 150 people–enough to work and support the local lord’s lands. A town might have 500 to 1500 people, while cities might be 2000 to only about 12,000, except for the capital of the kingdom. London itself never had more than 70,000 people in the Middle Ages, but Paris had a couple of hundred thousand, and Rome and Constantinople might have reached half a million.

Inns & Taverns

An inn was often a large house with a hall for dining and a few rooms for food (pantry and buttery) and a few private rooms. These were not hotels. Guests–even strangers–slept together in the same room and often in the same bed.

Inns always had overnight accommodations while public houses, alehouses, and taverns often didn’t. They all had a common room with small tables (often like tall benches) and a haphazard mix of benches, chairs, and stools but no bar; your drinks and food were brought in from a different room. These are important details that will make your fantasy taverns different from a Wild West saloon.

There should be no distilled spirits for sale. Aqua vitae was hard to make and considered a medicine. There was no whiskey, brandy, or other hard liquor. Your choices were ale (usually made on site), beer (which kept long enough to ship), cider (fermented from apples), perry (fermented from pears), and perhaps elderberry wine or grape wine. Grape wine was uncommon in England due to the climate but common enough elsewhere in Europe. So don’t think of a line of glass bottles on shelves; glass was too expensive for common drink. Think of small wooden casks.

And the piano was invented about 1700. It belongs in a Wild West saloon, but not a medieval or Renaissance tavern. You could have a harpsichord, tho, but the image below is an upright piano.

Bathrooms

Bathrooms on fantasy maps is a super-weird trend that completely baffles me. Ancient Rome may have had a sewer system with communal toilets, and Sir John Harington may have tried to introduce a primitive flush toilet to Lizzie Ace just prior to 1600, but modern-style bathrooms just didn’t exist until the 1800s and weren’t common until the early 1900s. (The White House didn’t have flush toilets until 1853.)

Well into the 20th century, even city folk often had outhouses, and the bath tub was a wash tub they dragged into the kitchen. As indoor plumbing became more common, city folk generally used a common toilet at the end of the hall.

And it isn’t necessary! The game doesn’t have any requirement for player characters to use the toilet. You can just leave it out and hand-wave it all as “a chamber pot by the bed and a privy out back”.

Food

A very common thing to overlook in D&D fantasy worlds is the food. Before the discovery of the New World, Europe had no potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, corn (maize), pumpkin, peanuts, chocolate, chili or bell peppers, or turkey.

People ate a lot of peas, beans, grain porridge, cabbage, onions, leeks, and lentils, as well as dairy products and eggs. They also ate a lot of nuts, in particular walnuts, hazelnuts (AKA filberts), pistachios, chestnuts, pine-nuts and especially almonds.

The peasants had little meat, and it tended toward rabbits, sausages, and bacon, while their betters got the roasts. They had temperate fruits (apples, peaches, pears) and, in more southern lands, some tropical fruit (oranges, bananas, lemons, limes).

Tea, coffee, bananas, oranges, and other exotic items from elsewhere in the world didn’t generally make their way to medieval northern Europe. And distilled liquor (whiskey) wasn’t invented until very late in the Middle Ages, altho medicinal distilled spirits where known in the High Middle Ages. The exotic–and very expensive–items that were known were like nutmeg, black pepper, cinnamon, saffron, mace, anise, garlic, tarragon, dill, and sugar (in hard, cone-like “loaves”).

It might be best to make up your own fantasy foods. That way, you can have people eat what you like without worrying about history. Have your people eat starchy pumlars and hagricots, sweet narpetos and sluberries, and exotic niclomits and vongles. You’ll probably want to still use real animals, like pigs and cows, chickens and geese. Just stay away from turkeys.

Or… don’t. You could just say “In my campaign setting, people discovered the exotic land of “Amerabia” 80 years ago, and its strange foods are being traded now.” Great, so you’ve got coffee (Africa & Arabia), tea (China), bananas (Africa), oranges (SE Asia, as with lemons, but lemons came to Europe much earlier), potatoes, chocolate, and pineapples in your campaign world–and an explanation for them that isn’t “Oh, I didn’t know they didn’t have that in medieval Europe.”

Goods

Lastly, other common mistakes are imagining that modern items would be available. Medieval Europe had little glass; what windows existed were stained glass and leaded glass, both of which use very small pieces of glass set in leading. The lower classes had shutters to keep the weather out of unglazed windows.

If you went to a shop, for the most part, you stood on the street and talked to the shopkeeper thru the open window. Glass windows weren’t even common until the 1500s, so they just had shutters. (Here’s a nice little collection of illustrations.)

Likewise, leather backpacks weren’t invented. Packs carried by travelers were typically either a leather or canvas haversack over one shoulder or a woven basket with shoulder straps. Another thing to note is the prevalence of baskets and barrels in place of crates. While wooden boxes, trunks, and chests existed, barrels are much simpler and therefore far more common.

Clothing

Again here, you are entitled to create your own fantasy world with its own fashion, but it’s good to understand the actual historical clothing and make changes rather than dress like an armored cowboy in trousers and a leather duster.

Some people may be shocked to learn that not only did clothing not have pockets (you carried a pouch or purse on a belt or shoulder strap) but Europeans in the Middle Ages didn’t even have buttons. Brooches and cloak pins are some of the most common items find in archeological digs from this period, but a lot of clothing was held together with pins until the 1800s. They did have belts, tho, often called girdles for both men and women, and they liked them very long and dangley.

Headwear was ubiquitous. The amount of uncovered hair in fantasy art and Ren fairs is strictly 1960s-and-on stuff. There were many styles over the years, so take your pick for your world, but the ubiquity of hats and hoods (often a cowl separate from the cloak, because England is a drizzly land) cannot be overstated.

Medieval clothing fashion was a bit dull, and we can be forgiven for preferring styles closer to the 1600s than to the 1300s. This is why they’re called Renaissance fairs and not medieval fairs. Even so, the biggest mistake remains full-length trousers.

Ankle-length trousers were worn in some parts of the world, usually in the form of loose-fitting pantaloons, for thousands of years, but the style thruout Europe was tight-fitting hose until hose were separated into knee breeches and stockings.

Second to trousers is jackets. Jackets, and indeed even coats, did not exist until the modern period. Cloaks were universal.