The photo above is of playwright/screenwriters George S Kaufman and Moss Hart.

© This material is not included in my open license.

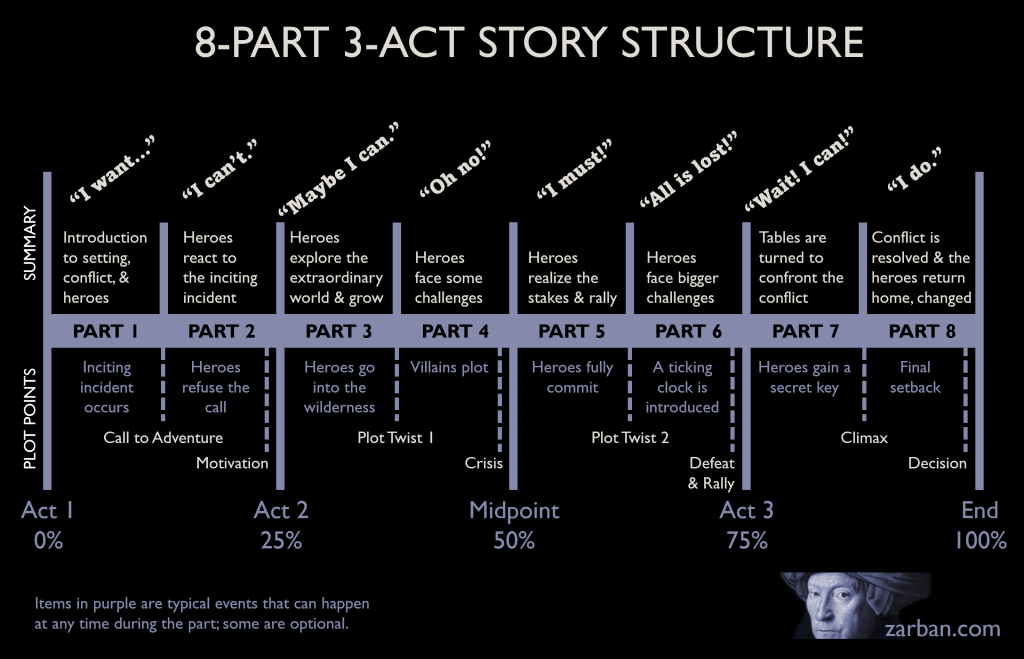

Last year, I wrote about 3-act structure. Now I’ll explore plotting. I’ve broken down each act into equal parts and listed the kinds of things than can go into each part. Many of these are just options; you can’t put everything in your story. They’re just reminders about the kinds of scenes that are appropriate for that section of the story.

In its simplest form, you can say that every 15 minutes of a 120-minute movie, you need a plot twist that changes the direction of the story and advances the plot. In between, you fill the pages with character development, exposition, and subplot.

Those twists need to present a problem, get the hero involved, get the hero into trouble, cause a crisis, cause worse trouble, bring the hero to a low point, resolve the conflict, and result in a decision that changes the hero’s life. And all the while, the hero is trying to get out of trouble. Every scene has to do at least one of three things: set the scene, develop character, or advance the plot. If many scenes do two or even all three of those things, we say it’s “a tight script”.

For each part, I give the approximate percentage of the story the events bring us to. If a screenplay will be 120 minutes long (120 pages), then at 25%, it should be on page 30.

But there are other things that happen in the story than just the beats. Character revelation, exposition, debates, fights, romance, etc. However, every scene needs to be in the story for a reason. It needs to fulfill or support a beat and be virtually indispensable. And a tight story is one that often has scenes that do more than one thing.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s method of doing this in the long-running South Park series is to ensure that every beat logically connects to the next one with therefore, because, and but, linking them inextricably. Of course, they primarily write 22-minute television episodes, which have to be extremely tight to avoid becoming messy, but the idea is a good one to keep in mind for longer form stories.

Other Factors

And while this treatise is just about structure, keep in mind that story structure is only part of the task of creating a good story. The other parts are compelling characters, good dialog, interesting setting, and setup-and-payoff. Audiences and readers will overlook many problems if they find the characters likeable, interesting, infuriating, or doomed. They’ll quote the characters if the dialog is good. They may get absorbed in the setting if it’s creative and deep. And they will swoon if dramatic moments are properly set up so they pay off big.

The short version of character development is this: A good hero has a want, a need, and a flaw. A good character arc has the character discovering that getting what they want creates a need for something else, and the thing they need can only be had by fixing their flaw.

Act 1

Part 1: “I Want…”

The setting, hero, conflict, and villain (often obscured or just mentioned) are introduced. At some point, the inciting incident occurs. At the end, the hero is confronted with the inciting incident in a call to action.

This part is typically not necessary in episodic story-telling; in a TV show, we know what the setting is and who the heroes are. So the story can begin with the inciting incident and move directly to part 2.

- The opening scene is often action or mystery, to hook the audience. It may be a prolog, which happens at a different time or place than the main story, or the hero is not involved in it.

- An on-screen legend and/or narration explaining the setting and conflict.

- The inciting incident the hero is not part of, such as the crime in a mystery.

- Something that happened in the past that is relevant to the story, such as the origin of the villain or the conflict or the main hero.

- A flash forward to a bizarre moment to come later, which the story will explain.

- A scene matched at the end with an epilog that “bookends” or “frames” the story. These put the story in context, perhaps suggesting it was all a dream or memory.

- The heroes are introduced. There is usually a main hero and supporting heroes, so it may be multiple scenes. (Heroes ideally undergo a positive change in the course of the story, except in episodic storytelling. Allies help but rarely change.)

- The heroes express a desire to leave the ordinary world or express some other need that will help drive the plot. This is typically the location of a musical’s “I want” song. Each hero may have a different need, but something brings them together.

- Plot point! The inciting incident occurs (if it didn’t happen in a prolog). Without this event, there is no adventure, and the heroes go on with their lives.

- A treasure may be introduced, such as money, letters of transit, or Death Star plans (AKA “MacGuffin“, altho stricktly speaking a MacGuffin has no use in the plot, whereas a treasure like the Death Star plans explicitly triggers the third act by producing the secret key). A treasure is a simple, external motivation, but it’s often introduced with the inciting incident, here or in the prolog.

- The heroes learn about and react to the inciting incident. This is the call to adventure, different from the inciting incident, altho they can happen at the same time (as the “meet cute” in a romantic comedy often is).

- Brings us to 13% (minute 16 of a 120-minute film)

Part 2: “I Can’t”

The heroes react to the inciting incident. At some point, they debate and may try to refuse the call to adventure. In the end, there is some motivation that compels them to take action anyway.

Again, this may be highly truncated in episodic storytelling. It may be the hero’s job to deal with the conflict (police detective faced with a murder or parent faced with a child’s misbehavior).

- The heroes react to and debate the inciting incident.

- The main hero often refuses the call to adventure initially, due to timidity, obligations, or a superior’s authority. This doesn’t mean literally refusing to engage with the problem but often dealing with it perfunctorily.

- The heroes take some kind of action or express desire to, but not to actually resolve the conflict

- The hero may be hampered by the perception that a superior must be convinced or that he or she doesn’t have the power or skills to engage with the conflict.

- It may be the main hero trying stay out of the conflict, such as by leaving town or reporting the problem to authorities.

- The heroes may get aid or advice from a mentor or similar ally.

- Plot point! Circumstance or the promise of a treasure gives the heroes motivation to take action to address the inciting incident (or less often the central conflict) and to fulfill their need.

- Brings us to 25% (minute 30 of a 120-minute film)

Act 2

Part 3: “Maybe I can.”

The heroes’ actions take them into an extraordinary world, where they undergo a change. At some point, they form a plan and go deeper, into a dangerous wilderness. At the end, they encounter the first plot twist.

- The heroes enter the extraordinary world, usually into a place of relative safety. This world can be their own world that has changed around them.

- The heroes undergo some sort of growth, becoming something more than they were before, perhaps by training or forming a team.

- Pressure is applied to the heroes in the form of a warning or ominous sign, close call with the villain’s henchmen, or some other complication.

- The heroes create a plan. This is plan A; plan A never works.

- The heroes leave the place of safety and venture into the wilderness. This the point where the heroes start to get more serious about resolving the conflict, perhaps taking matters into their own hands or otherwise going deeper or further into the extraordinary world.

- The heroes may meet:

- The villain in a social situation where action is not possible.

- A powerful person in a formal setting.

- A mentor, expert, or prophet in an unsettling setting.

- The villain reveals a plan to his or her henchmen.

- Plot point! The heroes are surprised by a plot twist that materially moves the plot forward, such as a meaningful clue, betrayal, secondary conflict, catch, complication, capture, death of an ally, or revelation of awful secret.

- Brings us to 37% (page 45 of a 120-minute film)

Part 4: “Oh no!”

The heroes encounter and have some success against some challenges. But at the end, they face a serious crisis.

- The heroes have a chance to catch their breath in a place of relative safety.

- This may kindle a romance or friendship. This typically follows the main plot points, with a crisis that immediately follows the crisis of the main conflict.

- The heroes reflect on the way their lives have suddenly changed. They may reevaluate their needs and be tempted to abandon the adventure.

- The heroes clash with a naysayer or wrong-headed superior.

- The heroes get a gift of or warning about a particular tool or technique (which draws attention to it, so it can be used dramatically in the climax).

- The heroes have partial success against the villain or some other complication.

- The heroes get what they need but it turns out to be partial, fleeting, false, or disappointing.

- The heroes capture the treasure (but it won’t last).

- The villains become fully aware of the heroes and take action.

- The villains may plot the demise of the heroes.

- Plot point! The heroes experience a crisis that threatens their lives or ability to resolve the conflict, such as:

- One of the heroes or an ally dying.

- The heroes being captured.

- The heroes suddenly facing a catch.

- The treasure being stolen.

- Brings us to 50% (minute 60 of a 120-minute film)

Midpoint

Part 5: “I must!”

The heroes realize the extent of the danger they face. At some point, they rally and commit to resolving the conflict. At the end, they face a second plot twist.

- The heroes react to the crisis.

- The heroes realize it won’t be as easy to resolve the conflict as they thought.

- The heroes rally and dedicate themselves to resolve the conflict and create a plan B. Plan B usually also fails, because the heroes don’t yet have the secret key to success.

- The heroes escape, if captured, or (try to) retake the treasure, if it was stolen.

- The heroes may need to sacrifice something (or they lose something equal to what they gain) to continue.

- Plot point! The heroes face second plot twist that materially moves the plot forward while also complicating it.

- Brings us to 62% (minute 75 of a 120-minute film)

Part 6: “All is lost!”

The heroes make more progress against bigger challenges. But at the end, they face a major failure or other defeat.

- The heroes deal with the plot twist.

- The heroes get another chance to catch their breath. A romance may blossom.

- The naysayer or wrong-headed superior causes more trouble.

- The villain and henchmen react to the heroes’ actions and take their own action.

- Plot point! The heroes suffer a major setback. A secret is revealed, the heroes are betrayed, and/or captured, etc. One of the heroes, an ally, or mentor is lost, dies, or is captured. A ticking clock may be introduced to spur the heroes on.

- The heroes have some success against the villain’s henchmen, but it is disappointing, hollow, or costly.

- The heroes hit bottom emotionally. It seems that all is lost and the heroes are defeated! But often there is a silver lining, and they (or some of the heroes) rally.

- Brings us to 75% (minute 90 of a 120-minute film)

Act 3

Part 7: “wait! I can!”

The heroes turn the tables on the villain. At some point, they gain a secret key to defeating the villain or resolving the conflict. At the end, the heroes defeat (or are defeated by) the villain, resolving the conflict.

While being defeated is quite rare in films and novels, it’s more common in episodic storytelling. In Gilligan’s Island, virtually every episode ended with a scheme to get off the island failing. In Pinky & the Brain, each episode ended with the characters vowing to try a new scheme the following night. In Red Dwarf, the heroes were defeated whenever the episode was about getting back to civilization. Even in serious TV shows, the need to reset the heroes for the next episode often means defeating their attempts at romance. The men of Bonanza must have lost a hundred loves.

- The heroes deal with the defeat, usually rallying as a result of a discovery directly related to the defeat.

- At some point, the heroes find the secret key to resolving the conflict, such as the villain’s weakness, identity, or location or a special device. It can sometimes be a secret from the audience and get revealed only when it is used.

- As a part of the rally, the romantic subplot (or internal team strife) may be resolved, creating a powerful partnership.

- The heroes come up with a new plan. The naysayer or wrong-headed superior may be overridden by a greater superior, or the heroes do it without permission.

- The tables are turned and the hunter becomes the hunted:

- The heroes take the fight to the villain’s lair.

- The villain’s henchmen capture the heroes and bring them to the villain.

- The villain turns and attacks the heroes.

- The catch is resolved, clearing the way to resolving the conflict.

- At the climax of tension, the heroes confront the villain.

- The villain may explain his or her evil plan or beg for mercy and/or justify his or her actions.

- The villain is defeated, often with the secret key, resolving the central conflict.

- The heroes may use a tool or technique they trained with earlier.

- The heroes may use a previously forbidden tool or technique warned against earlier.

- The heroes may produce a previously unknown document, clue, or surprise witness.

- Brings us to 87% (minute 105 of a 120-minute film)

Part 8: “I do.”

The heroes return home changed. At the end, the heroes make a decision about the future; this plot point is sometimes truncated, perhaps down to something as simple as “And they lived happily ever after.”

This is another part that may be entirely eliminated in episodic storytelling. Typically, characters don’t grow or change much in any individual episode (unless the episode makes a point of focusing on the overall conflict the heroes are trapped in).

- The heroes may deal with a final setback, perhaps pertaining to a secondary conflict.

- A henchman refuses to surrender and must be killed.

- A naysayer cites a technicality and must be outwitted and humiliated.

- The heroes are forced to flee the collapse of the villain’s lair.

- The heroes need to be rescued by nearly forgotten allies (deus ex machina).

- The heroes demonstrate that they are changed for the better.

- The heroes make a decision about the future, perhaps embracing romance or quitting a bad job. If there is a romance, the heroes declare their love.

- Loose ends are tied up, often in a brief epilog that takes place later.

- The heroes are congratulated, promoted, rewarded, or achieve new powers.

- The heroes prove they are changed by rejecting a reward or keeping a promise.

- One hero is visited in the hospital (or buried in a cemetery) by the heroes.

- The heroes may be tempted to (and sometimes do) remain in the extraordinary world, due to romance or an affinity for the culture.

- A deserving minor character’s need is met.

- The wrong-headed superior gets humiliated.

- The heroes settle into a new-normal life or see the culmination of their efforts in some other way.

- Brings us to 100% (minute 120 of a 120-minute film)