I wrote previously about many types of puzzles, some of which were environmental, but I didn’t describe them as such. These are a little tricky to implement in an RPG, because they are–or at least seem–very open ended. But because they’re integrated into the structure of the spaces where they appear, they’re also integrated into the theme of the adventure and so feel more natural and satisfying.

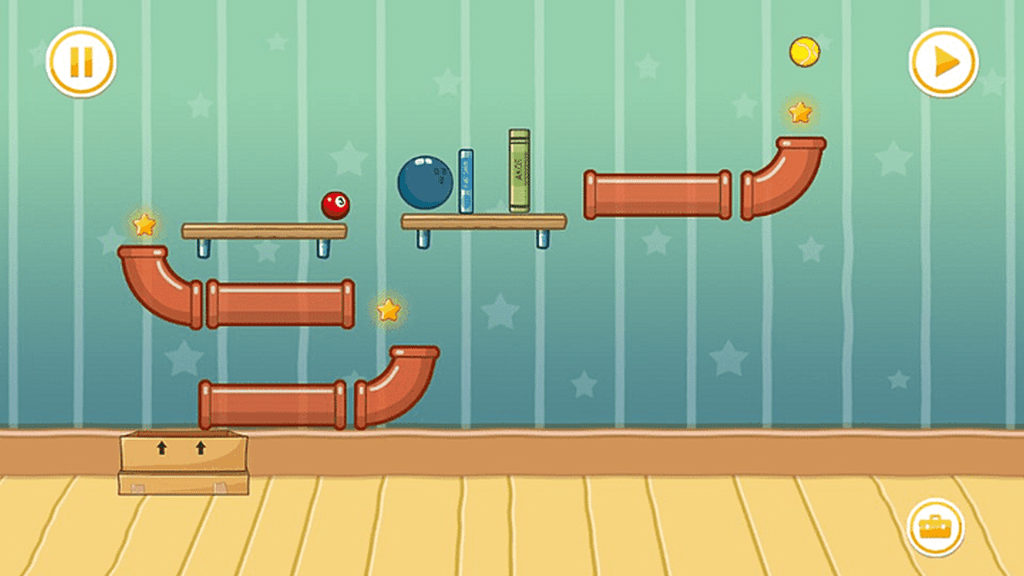

Environmental puzzles take the form of physical objects that must be moved, aligned, touched, etc. & that cause changes to the environment, such as opening valves, triggering lasers, & so on. These rarely exist outside of video games & RPGs, & are very common in video games (where they’re sometimes called “physics puzzles”, but that term is better applied to puzzles about vectors and forces).

Simple environmental puzzles can require the heroes to merely stack boxes to allow them to climb onto a platform or to arrange objects so that a kind of domino effect triggers a door to open.

There are typically a very small set of objects that can be moved or destroyed, levers and switches that change the state of some element of the room, and tools that produce an effect, such as the portal gun in Portal. Games like Portal are practically all environmental puzzles.

The hope with such puzzles–from the designer’s standpoint–is to generate an “ah-ha!” moment that makes the player feel clever for having figured out the setup that creates the proper sequence of events to get at the goal.

This is often achieved by presenting the puzzle in such a way that the solution seems straightforward but doesn’t work because of some obstacle. Then the player has to rethink things and try again a different way; but the initial failure provided the player with some crucial information about how the physics of the objects work. Then they have an epiphany about how to get around the obstacle.

There are typically hints about how things work called “affordances“: icons, colors, highlights, etc. that indicate the object is useful and how it can be used or activated. A button looks like it can be pushed; a lever invites you to move it. In the parkour game Mirror’s Edge, red objects can be traversed. In The Last of Us, subtle guidance is colored yellow. In an RPG, the GM can just emphasize useful things and points of interest.

They also tend to build up from simple puzzles to complex ones that combine the solutions of the earlier simple puzzles. Here’s a good video on it…

These sorts of puzzles are the most thematic and satisfying in an RPG. The player moves thru the world and uses items in it to create effects that are useful. And this creates “what have I done?” moments as well as “ah-ha!” moments. Ordinary table puzzles ported into the game feel artificial by comparison.

However, the integration of the theme (adventuring in a dungeon) with the puzzle (moving blocks or pulling levers) also introduces noise (in a communications sense, not acoustic sense). Is the wall sconce something I can use? Should I sift thru that rubble in hopes of finding a clue? Be aware of this and keep puzzle rooms fairly clean of distractions.

Example: The Pressure Switch

For example, the heroes move thru a dungeon and discover a room with a platform pressure switch that opens a door. But stepping off the platform closes the door. So one character can stand on the platform to allow the others to enter, but then that character will be left behind.

But previously in the dungeon, the heroes encountered large urns and also a well. The solution (or one solution, anyway) is to carry the urn to the platform and fill it with water from the well until it’s heavy enough to trigger the platform switch.

A 20-pound urn needs to be the size of a tall kitchen trash can to activate the 100 pound pressure switch when full of about 80 pounds (10 gallons) of water. Water weighs 8.3 pounds per gallon.

To make this easier, you could put the well and the urn in the same room as the platform and door. But it’s more satisfying to build up your players’ understanding: have a simpler puzzle earlier that requires the heroes to fill an urn with water for some other reason, such as to put water in a stone bowl mounted on the wall to trigger some other effect. Then, when they get to the platform room, it can occur to them as an “ah-ha” moment to use an “urn filled with water” again, this time as a weight.

Environmental Puzzles Mean Open Solutions

One thing to consider is that heroes often have access to a substantial amount of magic and could, for example, use a Dig spell to dig up the floor and pile that on the platform. Or they could drag the body of a dead monster to the platform.

As a GM, you have to be content to allow players to use their lateral thinking–which is what puzzles promote anyway–to resolve the predicament in a way you didn’t intend.

You also have to consider the fact the heroes might perversely smash the urns on sight because they’re suspicious they might hold danger. Later, with no urns to fill with water, they’ll have nothing to weigh down the platform. So you might need to say they can find one they missed.

In video games, the player often can’t smash an object they’ll need later, because, without a live GM, there’s no way to figure out if another solution (like a Dig spell) would work. Make sure that you maintain the value of a live GM by being flexible in ways a video game can’t be.

Leave a comment