In part 1, I explored the theory behind designing a dungeon. In part 2, I explore the various rooms your dungeons should have.

Categories

Dungeons should generally have 10 to 20 areas that are:

- Entrance (at least 2)

- Great Hall

- Storage

- Empty (several)

- Mysterious

- A puzzle

- A trap

- A small fight (at least 2)

- A big fight

- A vault

1. Entrance

Entrances typically have a guardian of some kind. In many cases, it may be a monster or literal guards, but in tombs and crypts it may be a puzzle or trap of some sort, or at least a lock. Secret entrances to a lair will be less guarded than the main entrance.

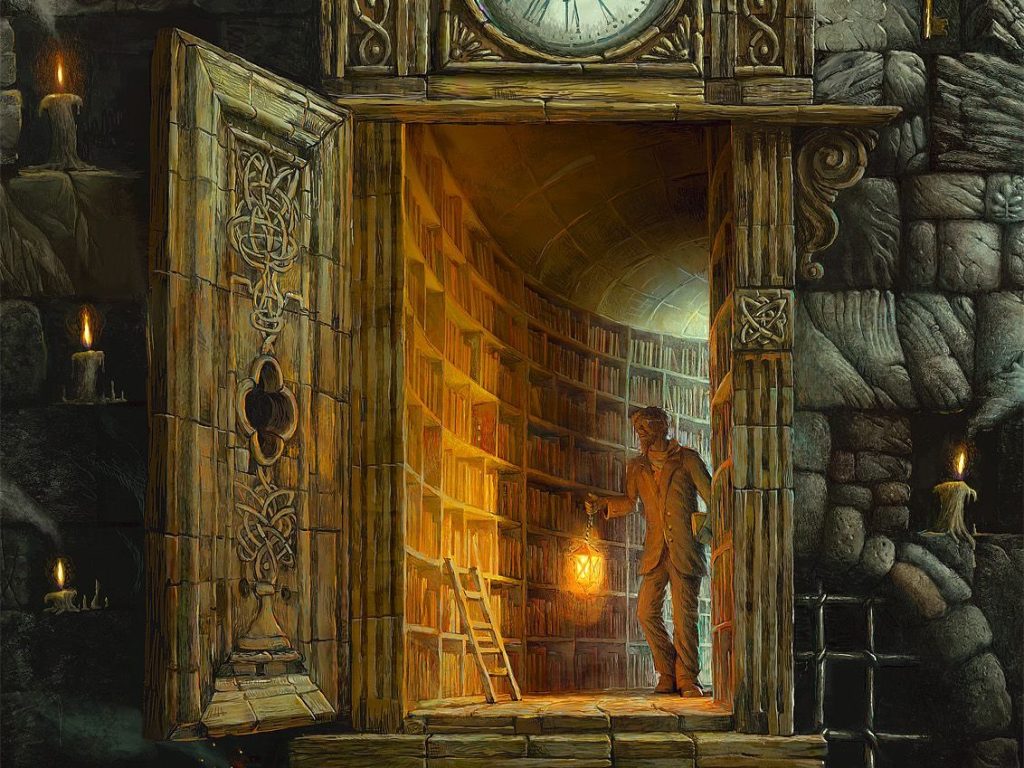

A cave mouth in a gully in the forest is fine now and then, but consider making your entrance a sinkhole that opens into the middle of a cavern complex, with any original entrance collapsed long ago, which is why it hasn’t been explored until now. Or make it a chimney in a ruins, leading down to a large fireplace, a hidden staircase in a surface ruin, or a magic portal found in some other location. Look for visual aids to make the moment the party delves into the darkness memorable.

For tombs and ruins and cavern complexes where the denizens don’t usually come and go out of the caverns, it’s okay for entrances to be three or four chambers that are essentially empty. Passages can wind around, chambers can feature forbidding carvings/paintings, and stairs can descend into darkness.

Give your dungeon multiple entrances, so the heroes can scout them out and decide which is the better choice. This really gives the players a meaningful choice.

For those entrances, consider not only ground-level paths but also entering from above or from underneath. If the heroes are going to explore a ruined castle, they might waltz thru the front gate or slip thru a secret door into the dungeon under the castle or go over a wall and thru a hole in the crumbling roof.

However, generally, don’t start your design with the entrances. Start with a centerpiece room that is one of the other types and which is two levels, or extra large, or specially guarded by monsters or a puzzle. Then design the other rooms around it and the entrances more-or-less last.

2. Great Hall

Halls are those created by the original inhabitants or the current inhabitants for the main use of the space. They are the most common rooms to have a second level, such as a balcony or mezzanine that overlooks the main floor or steps to a dais or other raised or sunken location.

- For a castle, it’s literally the great hall of the keep.

- For a lair, it is the common room, where most of the creatures live and sleep. Lesser halls include rooms where they cultivate mosses and funguses and whatnot to eat or to feed the creatures they eat.

- For a temple, it’s the sanctuary, where worshiping is done. Lesser halls include a back room where the priests or shamans prepare for ceremonies (or clean up after a sacrifice).

- For a crypt, this might be a single space used as a staging room, where bodies were left temporarily before being laid to their final rest, as well as a chapel, where a funeral ceremony was performed before the interment.

- For a dragon’s lair, this is the main space the dragon occupies, with lesser halls used to hold prisoners/livestock and minions.

These rooms are often not only large, but have an interesting layout, with a staircase to a second level, screens or half walls, columns to support the broad ceiling, statues, a well or fountain, etc. If there is a big stone face of the cultists’ god, maybe there is a space behind it where they can attack the heroes from.

They may be occupied or empty, but commonly are rich with information about what activity is going on in the dungeon. However, they are rarely trapped or include puzzles, since they are heavily used. They are also typically interconnected, for easy navigation; this gives the heroes more meaningful choices.

3. Storage

Everyone needs storage. These rooms tend to be small and out-of-the-way dead ends used to store foodstuffs, weapons, captives, ceremonial items, etc. They are rarely trapped but are typically guarded or at least locked (altho warlike creatures would likely keep their weapons handy.)

These spaces are rarely occupied, unless they contain captives and guards. They can be pretty informative and may even contain useful items the characters could use, including lamp oil, torches, a ladder, burlap sacks, or a shield.

4. Empty

A substantial number of chambers should just be empty–35% to 50% is appropriate. These offer a breather to the heroes and can serve to separate monsters who live in the same tunnel system (being a kind of no-man’s-land). (This goes back to Gary Gygax’s original principles.)

One way to design a dungeon is to draw the main locations wherever you like and fill in the spaces between them with empty rooms and passageways afterward. Or create a big, grand hall that is empty (or a mystery; see below), while surrounding chambers are where the perils lie.

These spaces don’t have to be completely empty, of course. They may contain rubble from cave-ins, ceiling collapses, or recent tunneling; interesting rubbish the denizens don’t want; the bones of the dead. Let the “emptiness” fuel the mystery and create suspense.

- Perhaps the mushrooms growing on some old wood can be identified by a druid as useful for curing certain diseases the heroes may contract elsewhere in the adventure. (Overly convenient? No, logical: occasionally eating the mushrooms is what keeps the denizens from dying of the disease.)

- Perhaps there are stone blocks or a water pool that become resources when the heroes realize a puzzle or trap in another room needs a heavy weight or some water.

- Perhaps the tapestries tell of the history of the dungeon or at least reveal the original builders or even reveal how to find the treasure. “The high priest appears to be passing thru a wall at the back of the temple, where gold treasures lie beyond.”

Corridors can be considered empty chambers. Small creatures should often create small corridors. Grand organizations should have wide corridors for general use and small corridors for side chambers and private areas. Natural caverns (and natural caverns that have been enlarged for someone’s use) tend to have really unusual layouts, including ledges and such. Note that players tend to ignore small side passages in favor of large main passages.

5. Mysterious

Most dungeons and other structures will have rooms that are a bit of a mystery as to their purpose. They may be disused because the space is flooded, ruined, unstable, etc. They tend to point to the original builders and the dungeon’s original purpose and can often be the richest in information about the original inhabitants. They can be covered in carvings/paintings/tapestries that tell a story of its original purpose or feature statues meaningful to the inhabitants or former inhabitants.

They tend to be out of the way and unoccupied but can be of any size. If one is occupied, it’s typically by something that predates the current inhabitants, like a golem or other construct. Or something has moved in afterwards but the current inhabitants can’t remove it, like giant rats, giant spiders, ooze, or mold.

Such chambers are the most likely to have the weirdest artifacts in them, such as a portal, a talking statue, or a strange puzzle or clues to a puzzle elsewhere. And this may be why the room is not used by the current inhabitants of the complex.

These rooms may be dead ends but they may also be connected to multiple other chambers (or a whole other, deeper dungeon complex) but possibly blocked by the current inhabitants, if the spaces are considered off limits or dangerous. Again, they provide more meaningful choices to the heroes.

These are good places to have a shaft of light from some air vent or skylight, eerily illuminating some mysterious thing. An alternative entrance might lead directly here. Or, on the surface, it can be hidden, barred, or otherwise less than ideally accessible to keep intruders from finding them easily (or else they’d be a primary entrance).

A 30-foot surface building’s doors are blocked by foliage and fallen stone, but the roof has a skylight that allows light down thru the collapsed floor to the ancient temple’s main chamber. But the skylight is crisscrossed by strap iron to keep burglars out, so even if the heroes thought to climb onto the roof, it would take them hours to break enough iron to slip thru, and then they’d have to climb down a rope 65 feet to the floor, one by one.

6. Puzzle

Puzzles are a great way to avoid a dungeon crawl becoming a dull hack-and-slash exercise. I’ve written a lot about them.

In a lair, a puzzle might revolve around how to fool or distract guards because fighting them would raise an alarm. In a crypt, a puzzle may serve as a kind of guard, not letting uninformed intruders pass. It may be the same case in a temple, or a puzzle may serve as a way to awe the faithful with secret knowledge that may seem like magic.

Sometimes the puzzle is just a matter of figuring out the “rules” of the room. In a temple, an antechamber may require the faithful to bow or make the sacred sign to open a door or avoid injury. Or a puzzle can involve merely moving the furnishings so they block a door from automatically closing after you pass thru it.

A puzzle room is rarely occupied, unless the occupants (such as guards) are part of the puzzle. However, fighting the guards and working a separate puzzle at the same time might be a good challenge. Perhaps the guards can move levers to raise and lower portcullises or divert water into or out of the chamber.

However, sometimes a creature can be a puzzle, such as an NPC who may be a captive or an ally of the denizens or a creature that lives in the dungeon and is neutral or perhaps even a foe of the main denizens and could be persuaded to help the heroes.

7. Trap

In the case of a lair, traps tend to be out of the way of normal traffic, to avoid accidents. For a temple or crypt, trapped chambers or corridors may serve in place of guards in key locations.

As with puzzles, such locations are rarely occupied, unless guards are part of the trap or captives are the lure. Guards might be able to lower a portcullis or lock a door to trap the heroes. Or they could attack from behind thru a secret door. Or the occupants could be trap-type creatures, such as a mimic, piercer, or similar creature.

Also, like puzzles, traps may not be purposeful. The creators may have designed the chamber to their needs, and it may only injure or entrap foolish intruders who don’t know how to activate the exit. Or a bridge or flooring may have become decrepit and prone to collapse.

8. Small Fight

Here and there in the dungeon, there should, of course, be minor encounters that turn into combat. Some of these can be isolated, but some should depend on how much noise the heroes have made, including in other fights.

The opponents can be common denizens of the place, guards, minions of the boss, creeping undead, etc. Note that this includes such things as a gelatinous cube or otyugh that the “owners” of the dungeon aren’t allied with.

9. Big Fight

Deep in the dungeon (so, near the end but not actually at the end), the heroes should encounter a major battle with the denizens of the place. This might be the boss of the inhabitants of a lair, the high priests in a temple, or the most powerful undead in a crypt.

These sorts of combats should usually involve minions of the boss. Relying on a single creature–no matter how powerful–allows the heroes to focus their attacks, flank the opponent, and take chances they couldn’t afford to take if there were more than one opponent.

These chambers tend to be out of the way but not dead ends. Bosses may have an escape tunnel or magical means of escaping, so that they may come back for revenge or merely deprive the heroes of a complete victory. These escapes should be foreshadowed, if possible, and perhaps even defeatable, if the heroes are clever. The escape route should not merely be another entrance, or the heroes could stumble on it and avoid the entire rest of the dungeon.

10. Vault

The bad guys usually have a treasure of some sort, and the location where it is kept is typically guarded by actual guards, a trap, or a puzzle. They are typically located near the boss’s chamber but out of the way and not connected to many other chambers.

Lairs will typically have actual guards, altho they may not fight if their boss has already fled or been killed. Crypts and tombs, in addition to or in place of a trap or puzzle, can use constructs or other animated monsters or creatures in suspended animation or summoned from another location or plane. It may even be a combination of such elements, like a stone golem that can ignore the toxic mold that will put heroes to sleep if they fail a saving throw.

Of course, “treasure” here can mean whatever goal brought the heroes into the place: gold, magic, knowledge, captives, the fight with the Big Bad Wolf itself, etc.

Leave a comment