I wrote previously about Myst and Riven. You can use some of principles from these games in your fantasy RPG campaign. In fact, that’s how the Miller brothers tested their ideas before starting production.

Your players already expect to roam around a dungeon or wilderness map. Consider designing areas that have a specific, mysterious purpose that the players can puzzle out. This means adding elements that can be manipulated and, once manipulated, modify the environment.

This leads to “Ah-ha!” moments that players treasure and that further lead to “What have I done?” moments as they change their environment. If your heroes’ actions don’t have effects and consequences, it doesn’t seem alive. It’s a museum instead of a playground.

Concepts

There are a few basic concepts for integrated puzzles:

- It’s obvious that something can be done but not obvious what.

- It’s obvious what to do but not how.

- It’s obvious how to do something but not why.

You need all of these for it to be successful. If the players don’t recognize that your room or device is interactive, they won’t try interacting with it. If they can’t figure out how to do so or why it would be helpful, the encounter will fail.

But each of these can be satisfied by different clues. After all, if all three are obvious at the same time, there’s no puzzle to solve.

Apparent Usefulness

Generally, the less obviously puzzle-like and the more machine-like, ritual-like, or recipe-like these interactions are, the more they feel integral to the setting. Things should work the way they do because that’s just how they were designed for their purpose; it’s a puzzle because the heroes haven’t been trained how to use it. Poorly-labeled buttons, garbled messages, tattered notes, and such just add to the mystery while helping just enough to make the predicament solvable.

But keep in mind that it serves no useful purpose for there to be a bunch of choppy-crushy things in the middle of a hallway.

Clues to the Method

Helping heroes work out how to interactive with a playground requires clues.

- The way it works is somewhat obvious (dangerous, because that’s very subjective).

- They are told or read about it being used.

- It reacts to their mere presence.

- They see it being used (live person, ghost, in a piece of art, etc.).

The method used in video games is usually to present a very simple example of the puzzle early on, so the player understands the workings. Then you can present trickier versions later, confident the player understands the basic workings.

To do this in an RPG, have a very simple, low-stakes, low-reward version of the puzzle early on. For example, in order to open a door, the heroes have to place a statuette of a nymph with a bucket in a little niche with a well, but that nymph statuette is sitting on a table right next to the niche. Later, when they find a niche decorated with bear cubs in a den, they’ll know to go looking for a mama bear statuette. And at the end, when they find a niche decorated with demons drinking blood, they’ll search for a demon statuette and, when it doesn’t have blood on it (and doesn’t work in the niche), they’ll slowly realize they need to provide the blood themselves….

Grasping the Reason

Motivating the heroes to interact with something may not require much.

- It’s interesting and doesn’t seem dangerous.

- They are told or read about the reason to use it.

- It looks like it does something valuable (dangerous, because that’s very subjective).

- They see it accomplish something for someone (live person, ghost, in a piece of art, etc.).

Examples of Playgrounds

I’ve written up several playgrounds in detail. Your mini-mysterious-island can be any number of things:

- A room containing tools useful for fixing something in another room.

- A magical laboratory with ingredients or equipment that can be manipulated to achieve some effect and a journal of notes to help.

- A journal that contains clues or a small library containing useful lore. (Perhaps with a sentience or a spirit librarian.)

- A room of pools, with valves allowing water in and out for some purpose.

- A ship that contained some escaped monster, with clues as to its type and whereabouts.

- A temple with statues that can be arranged too accomplish something, with clues in the murals on the wall.

- A room with barrels that can be moved to allow the heroes to climb to a location formerly reached by a ladder that is now broken.

- A garden of strange plants that can be interacted with and statues or furniture that can be manipulated to some purpose.

- A gallery of talking statues or portraits that can be questioned for clues and perhaps moved and used to solve puzzles.

- Magical artifacts that can be combined, connected, or arranged in a systematic way to achieve various effects, one of which solves a problem.

- A strange creature that can be talked to and negotiated with for help.

- A room with a mural on the wall containing hidden figures (small birds, etc.) that must all be found and touched to activate something.

You can even create whole adventures with very little combat, where the heroes just explore a mysterious location:

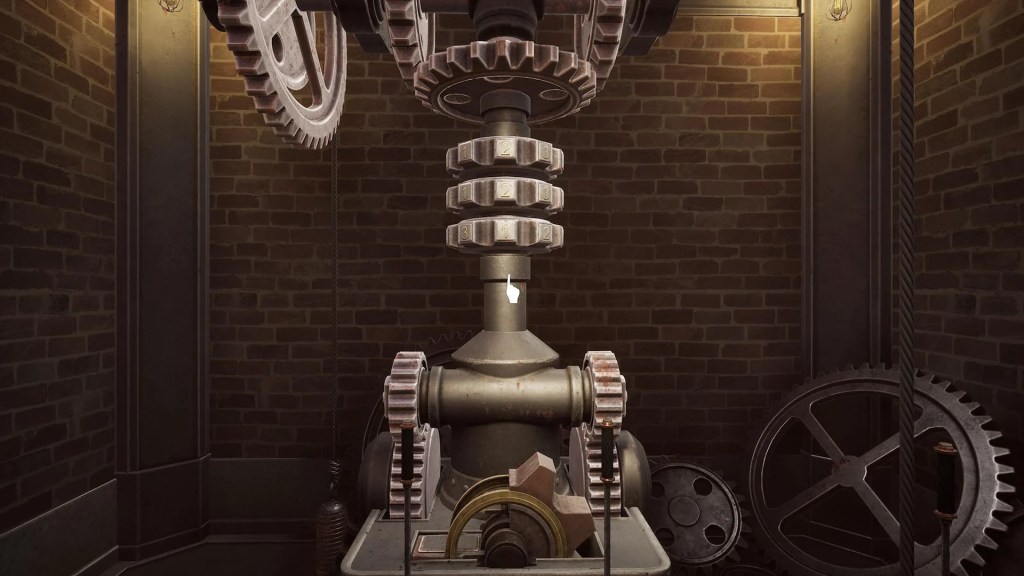

- An artificer’s castle, with mechanical devices of mysterious purpose.

- A dwarven mine, with a mechanical elevators and such.

- A clockmaker’s tower, with clocks and automatons to interact with.

- A locksmith’s stronghold, with puzzle and combination locks.

- A ruins destroyed by invaders, with clues to their identity and/or the location of survivors.

- The temple of a god of chance or cleverness, with games and puzzles to prove the heroes’ worthiness.

Steps

Once you get clues to what, how, and why, you can backtrack and do what you need to do, but that may entail certain extra obstacles:

- Assemble the pieces.

- Repair the device.

- Activate the system (turn on a water valve, disengage the brake, etc.).

- Find the password.

- Adjust the settings correctly (orientation, water level, weight, etc.).

- Trigger it without being in its area of effect.

- Trigger it without being able to see it.

There can be just one or several steps, each quite simple in itself. For example:

- This device we found obviously has some purpose, but what?

- This note mentions a star-finder device, so it must find stars, but how?

- A book shows how to set the star-finder to align with a constellation, but why?

- The ritual on this scroll that summons help against these monsters requires we be aligned with the right constellation. Quick! Get the star-finder!

Note that there’s no particular order to finding the answers to these things. The heroes might learn they need to align with a constellation for the ritual, then learn that a “star-finder” will let them do that, and then find the device. Or they could find the mystery device, then learn they need to align to a constellation, and only later put two and two together that the device finds stars.

Don’t rely on the heroes doing things in a certain order.

Consequences

Of course, skipping a step can lead to not knowing what you’re doing, which can have serious consequences, such as:

- Alerting enemies.

- Trapping you.

- Summoning a fiend.

- Teleporting you.

- Flooding a location.

- Starting a fire.

- Releasing something that is captive.

Even doing the right thing can sometimes leave you with negative consequences. Investigating enough to understand those beforehand can allow the heroes to prepare for them. If its use will draw attention, for example, they can be prepared to hide.

Leave a comment