I’ve written previously about creating taverns, inn, and alehouses. Your campaign world doesn’t need to match historical medieval or Renaissance Europe, but it also shouldn’t be a random conglomeration of fiction tropes.

Alehouses

More or less every village had an alehouse. They were literally just the home of whichever woman (an “alewife”) often brewed ale. It was traditional to hang a broom outside to indicate a brew was ready, in part because ale does not keep well. (In some places, hops was added to ale, making it beer, as a preservative, giving it a distinct flavor of its own.) In Britain, they would also offer wine, typically in the form of cider (apple wine) or perry (pear wine), but grape wine was available in continental Europe, where the weather was better for vineyards.

These places were mostly for locals to enjoy a tankard or bowl but were occasionally patronized by passing travelers. After all, village were tiny–often less than a hundred people–because they only served to house those who tended the fields of the local manor. An alehouse rarely offered any food or overnight accommodations.

Taverns

Multiple taverns could be found in any town or city. They were typically one large room, and the owner lived in rooms above it. They generally offered ale, beer, cider, perry, grape wine, and sometimes other wines, such as elderberry. These also did not offer food or accommodations, generally, except for snake foods, like nuts, bread, and cheese.

There was typically no bar or counter, per se. Casks of drink were merely put in a corner or mounted on racks to one side, and patrons were served at tables scattered around.

Where people are drinking, there is typically also entertainment, so musicians (mostly local amateurs) would play for those who wanted to sing along or dance. Such places naturally also attracted women with loose reputations.

By the Renaissance, taverns had begun offering food and accommodations, making them rival inns.

Inns

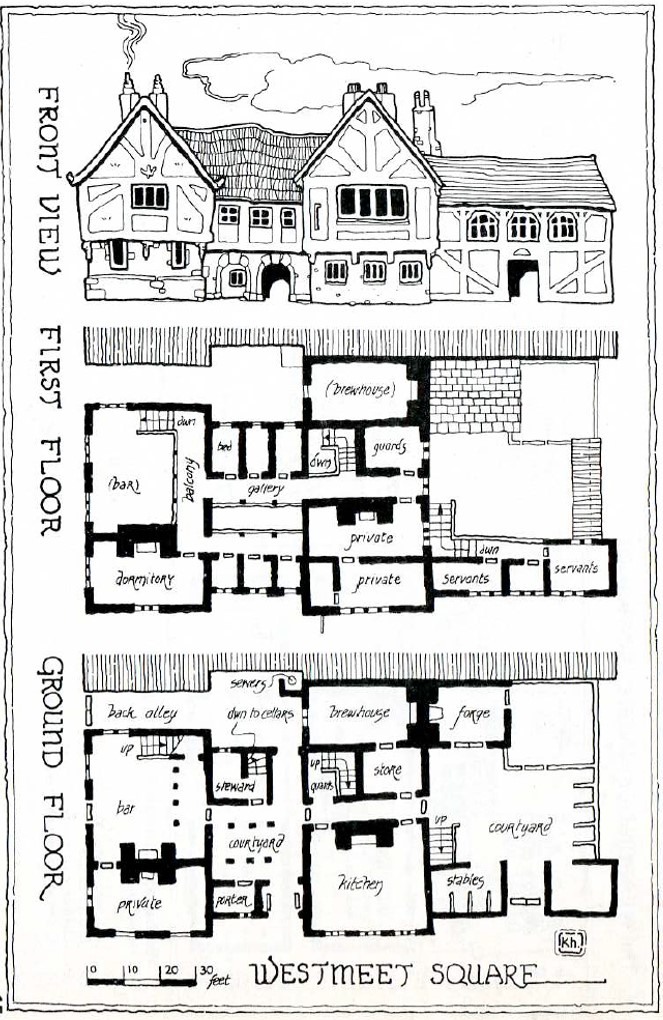

An inn was an establishment that primarily offered overnight accommodations. They tended to be fairly large, with rooms for the owners as well as several rooms to rent out and a large room on the main floor for dining. They typically offered food but only what the innkeepers had prepared–altho a few choices might be written on a chalkboard (in French, à la carte means “from the board”).

Inns had stables and, usually, a courtyard. Guests stayed in a dormitory room or semi-private rooms, often with strangers–sometimes in the same bed, if they traveled alone. Possessions could not typically be left behind for very long with any expectation of safekeeping. Large inns might have more than one hall, one of which might even be used for local meetings, such as a debtors’ court.

Coaching inns were those that grew up on longer legs between cities and so catered to longer-distance travelers. By the Renaissance, inns had begun catering to drinkers, making them rival taverns.

Feasts

Not a business but certainly common in the Middle Ages were feasts. These were prepared for any special gathering or for their own sake, particularly by wealthy people.

Typically, a lord would serve a feast in the manorial hall, where trestle tables would be assembled and set. (Since the servants and in some cases the lord of the manor also slept in the hall, the trestles would be put away afterward.) The guests would be served various dishes from large trays by servants. There might also be entertainment in the form of minstrels, dancers, and such. Formal dancing by the guests would often follow.

Such events were held to honor saints, deals, marriages, honorable deeds, homecomings, victories, etc. So speeches, toasts, and announcements were commonplace.

Leave a comment