Several months ago, I posted about my Battle of Wits method of resolving opposed negotiations and disputes in role-playing games. But this mechanic is actually quite useful for other kinds of situations, namely skill checks.

Skill checks were introduced in 4th Edition D&D but weren’t well explained, and people largely ignored them, especially since they were taken aback by the massive change 4e presented from previous editions of the game. But since then, certain YouTubers (Matt Colville, Dungeon Dudes, Dungeon Coach, the DM Lair) and others have championed the idea as useful in any system. But it occurred to me that the structure that skill challenges lack can be provided by tic-tac-toe. Bear with me….

Battle of Wits Summary

Battle of Wits is a mini-game in which the players choose arguments and methods to try to make points with an opponent, audience, jury, or judge to win them over; it plays out as a game of tic-tac-toe. Since the taking of each space (making a rhetorical point) is an opposed skill check, play isn’t as simple as a normal game of tic-tac-toe.

Skill checks are the heart of skill challenges, so all a game master has to do is play the other side of the game as the “circumstances” the heroes face, and the result is that the heroes succeed, fail, or find themselves in a no-man’s-land of neither.

In an OSR system without skills, you can use intelligence, wisdom, and charisma checks to inform, educate, assert, intimidate, deceive, impress, entertain, etc.

Standard Skill Challenges

Typically in a skill challenge, the players propose how they might use their skills to accomplish the overall mission, the GM approves them, and the players proceed to make skill checks as the GM describes the successful or unsuccessful results. If the heroes accumulate three failures, the party fails the challenge. If it’s a difficult challenge, they may need several successes to succeed at the challenge.

Not every hero needs to perform a check–some challenges may be mostly physical and some mostly mental. But they should be varied so that, eventually, all the heroes get to shine in some challenge or another during the campaign.

Escape the Crumbling Keep!

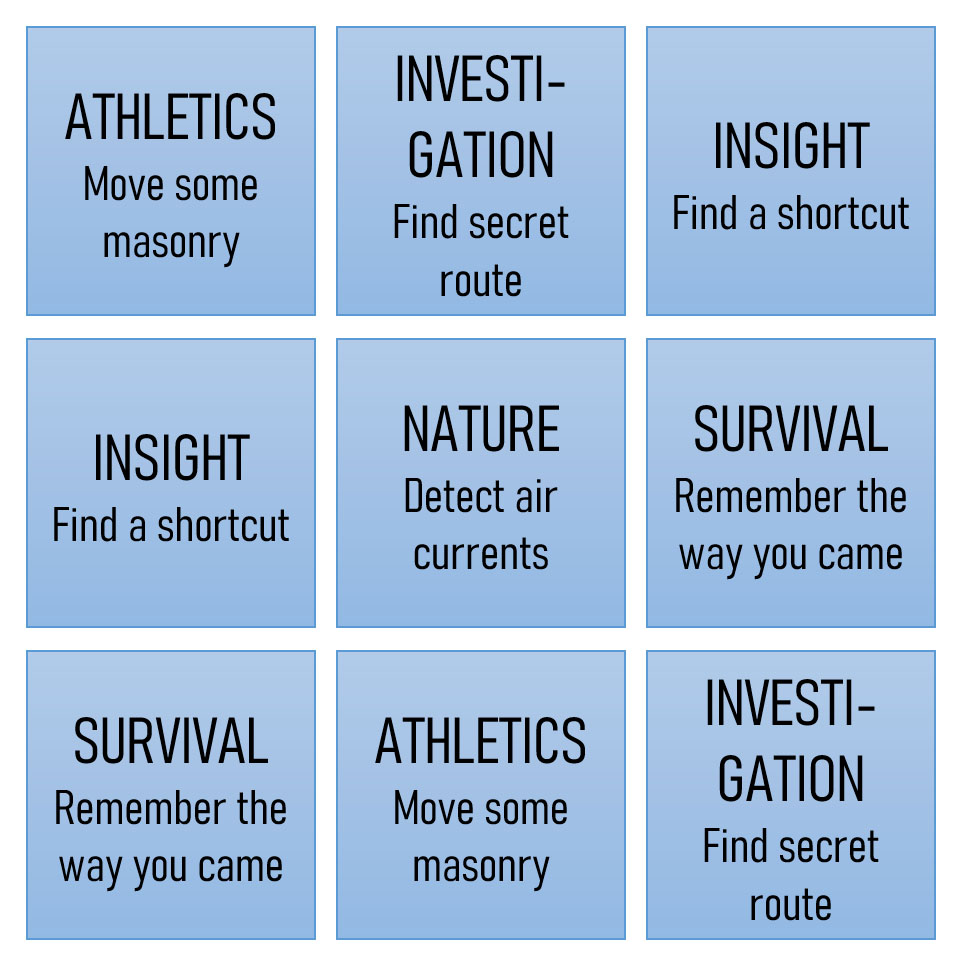

In Matt Colville’s video, his first example is heroes trying to escape a crumbling keep after killing the evil overlord; this would be tedious to play out on a map, movement by movement, but by letting them roll individual skill checks, all the players got to be involved in a dramatic escape. He told them three skills that would definitely be useful (survival, to remember the way they came in, insight, to find a shortcut, and investigation to find hidden exits) and they thought up more (nature, to discern fresh air currents, and athletics, to move a fallen chunk of masonry). This seeds the players’ minds with possibilities but requires them to come up with the ways to finish the job.

In an OSR system without skills, you can use dexterity to leap over obstacles, strength to move them, intelligence to find alternate routes, and even dwarvish abilities to sense slopes and crumbling stone.

Grid Skill Challenges

As a tic-tac-toe minigame, you can seed some of the boxes with skills–including spells–that can be useful and let the players help populate the rest. Then you play out the game, with the players having some choice as to which checks to make, but constrained by the board’s layout to get three-in-a-row. Only a character proficient with the given skill can try it (altho others might be able to help, giving the character a bonus), and a given character can only try a given skill once (altho you could try the same skill in a different square).

A single failure could have consequences; in his example, Matt said that failing a check meant standing around too long, and a piece of masonry could hit you. He allowed characters to then perform additional checks (acrobatics to avoid it or perception to push someone out of the way) to mitigate the failure.

Playing the Other Side

As GM, you make choices of your own to stop the players–either representing mere chance or fate introducing drama or representing the bad guys actively trying to thwart the heroes.

- If random events are closing off certain options (the keep crumbling around the heroes), make your moves randomly (rolling a die or selecting from chits), which automatically takes the square.

- If the heroes’ actions are actively opposed or competed with (trying to stop a ritual with NPCs are trying to complete), play to win, but make checks for the NPCs to try to take squares.

You need to decide if certain squares can be overturned by the heroes (or even the GM) under certain circumstances. Generally, as with the Battle of Wits, this should only be allowed one time per square at most, and perhaps only one time per challenge. Either way, it should be harder to overturn a square than to win it in the first place.

However, if you’re rolling randomly, you may want to decide that fate has overturned one of the heroes’ successes and sealed that move after all; I mean, they’re playing tic-tac-toe against random die rolls; it needs to be a little tough. But, if failure means certain death, you need to keep the challenge on the easy side.

You, of course, need to explain what’s happening in narrative terms: you make your way to the door, but a piece of masonry falls and blocks it; lacking a better option, the heroes try to move the masonry–now a strength check to open the square and then whatever the square’s check was before. Or the square changes to a different, harder check or perhaps it keeps the same check but the heroes get -2 to take it over.

Filling in the Grid

While it shouldn’t be too difficult to come up with enough skills to populate the grid, there’s no reason you shouldn’t allow a skill to appear more than once. It’s best to place duplicates in squares that don’t make three-in-a-row with any third square, so a success must be with three different skills. You can do this with as few as five skills, like those mentioned above.

Remember that you can also use spellcasters’ spells to fill in a square, such as using levitation to lift an obstacle out of the way; this burns the spell, of course.

The advantage to this method is that the drama is ramped up as certain avenues to success are closed off by the GM’s moves. It’s not enough to merely think of a way your skill might be useful; you have to find an opportunity to use it. It creates a strategic demand beyond mere dice rolling–even tho that strategy is merely tic-tac-toe.

Other Examples

- Heroes trying to leave a location will have to fight more guards at the exit depending on how many skill checks they fail in a skill challenge.

- A moonlit chase across rooftops using acrobatics, insight, and athletics skills, among others.

- Stopping a ritual of summoning using religion, arcana, healing, and medicine.

- Slowing down the progress of a huge monster the heroes aren’t powerful enough to fully stop.

- An investigation of a mystery using investigation and perception. Successes accumulate clues.

- A search of an area for a specific thing using survival, insight, and perception. Failure results in unexpected combat.

- Defeating a trap or mechanical engine using thief abilities, tool knowledge, and perhaps arcana.

Leave a comment