Tips for drawing maps for fantasy worlds.

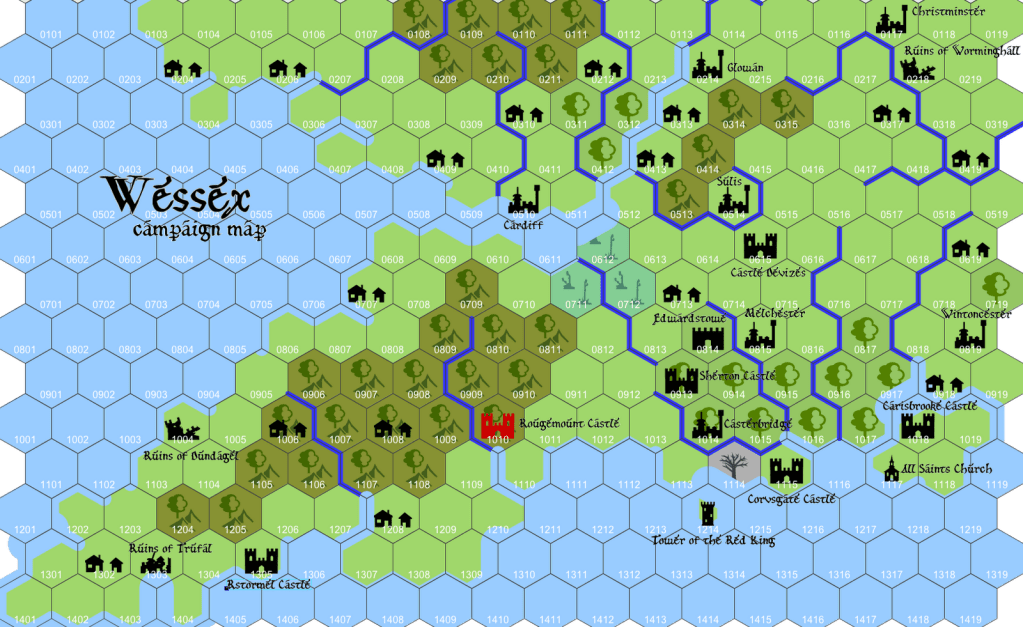

Scale

Don’t draw a map without a scale. It’s weirdly common in the RPG hobby. The scale of map most relevant to the heroes should grow with them. At first level, it might be just a 1-mile hex: go to the scrub lands away from town and fight the goblins. At 3rd-level, they graduate to a 3-mile hex. At 6th, to a 6-mile hex. At 9th, to a larger scale to encompass the whole realm.

You don’t have to have the whole realm mapped at the start of a campaign, altho you can share rough drafts with players. After all, any map the heroes themselves would see would be crude and full of mistakes anyway.

As a general rule, any major point of interest on the map should be found by the heroes when they enter the hex it is in. Otherwise, it’s hidden and probably shouldn’t be on the (player-facing) map; but it could appear on a smaller-scale, local map.

Note that “searching” an area is most efficiently done by visiting towns and asking where the ruins are; the locals (especially shepherds) know their area quite well, even if they’re afraid to actually visit the ruins.

1-mile Hexes for Initial Adventure

In a fully settled area, the great majority of land is manors belonging to lords: fields and pastures with a bit of managed woodland (called “parks”). Each manor and village would take up 3 or 4 hexes, and some manors are actually multiple manors grouped together. But it’s unlikely you would want to map settled lands at the 1-mile level. It would be all fields and towns; and people travel mostly by road, not cross-country. And there wouldn’t be many ruins or monster lairs, and certainly no need to search for them; the locals could lead you right to them.

A borderland map will have a few towns surrounded by fields to partially support them and various forest, wasteland, and prominent hills, as well as some open moorland, fens, and such. Much of it would likely be the king’s own land, but any settlement would be close around a small castle the peasants can retreat into when attacked. Raising animals (for wool, milk, meat, and as steeds and draft animals) is the principle occupation in such areas.

The local shepherds will know the area–and its monsters–very well, but they may not know exactly where the monsters’ lairs are. So the heroes will have to explore and look for clues (tracks, hunting parties, temporary camps, etc.). It’s ideal adventuring territory.

A 1-mile hex map of an uninhabited area may be primeval forest, hills, open moorland, fens, grassland, and such, also mostly the king’s own land. This land was likely a borderland or even once a settled land before a war or plague, and will likely have some ruins and monster lairs for the heroes to find. The heroes would presumably go to such a place to explore one particular ruins or monster’s lair, so it doesn’t need to have a lot of points of interest.

You can travel three hexes of clear terrain (road, moor, or grassland) per hour and travel for about 8 hours a day, so you could do quite a lot of wandering here in a couple of days.

3-Mile Hexes for Low-level Adventure

If you’re ready to let the characters explore the wilderness around your initial starting area, your scale may be 3 miles per hex. These hexes are small enough to see across–especially from a hilltop–and walk across in 1 hour, so it’s strictly for exploration; long-distance travel is going to walk right off your map.

In a settled region, there would be one or two manors with villages per hex. There’s a limited variety of terrain at that scale (that is, many nearby hexes will have the same terrain). Cities being 18-24 miles apart, there might only be four cities on your map, each taking up its entire hex to house 2000-6000 people. Towns are 6-12 miles apart, so there would be one every two to 4 hexes, housing 500-1500 people.

You can cross a good-terrain hex in 1 hour. Good for exploration. This is a good sort of map to start a campaign, because there are lots of low-level adventures to be had in a small area. But as the characters advance, they’ll need to do some traveling to find worthy opponents.

If you put ruins on the tops of hills (where they are typically found), the heroes will be able to see the land around for perhaps two hexes (rather than the one they’d see on flat ground) and could spot another point of interest on another hill perhaps three hexes away. Populate your map accordingly.

6-mile Hexes for Heroic Adventure

For travel over roads, the most common map scale for adventure games is the 6-mile hex. This documents a substantial part of the realm. There would be around 14 manors in each settled hex, a town every hex or two, and a city every 3 to 4 hexes. Therefore, don’t bother mapping villages or towns–just cities. Pull towns and their NPCs at random from a pre-made list. Add small cities to the map only when you need them.

People can walk 3 hexes a day on a road. This should not be surprising: in a society where everyone walks everywhere, they naturally settle so that everyone is within half a day’s walk of a market town and a days’ walk of a city. Good for point-to-point travel.

Whole-realm Maps for Epic Adventure

At higher level, you might graduate the party to a map of 10 or 14 miles to the hex, but it’s more practical to move to a whole-realm map instead. At 14 miles and larger, nearly every hex would likely include a point of interest (at least in settled areas). To avoid plastering the map with towns, cities, castles, and ruins, you would need to start ignoring lesser points of interest, like ruins with low-level monsters and all towns. There would still be a city every 2 to 4 hexes in settled lands.

Whole-realm maps don’t need hexes but still benefit from a scale so players know how many days’ travel it is from place to place. These are appropriate for high-level characters who need to travel between cities and need to know what realm borders what other realm and what part of the coast would be good for staging an invasion.

Once they’ve reached the general area where a certain ruins is said to be located, they can just ask around and learn from the locals exactly where it is. At that point, you can switch to a smaller-scale map (maybe even 1-mile hexes) for the adventure itself.

Furnishings

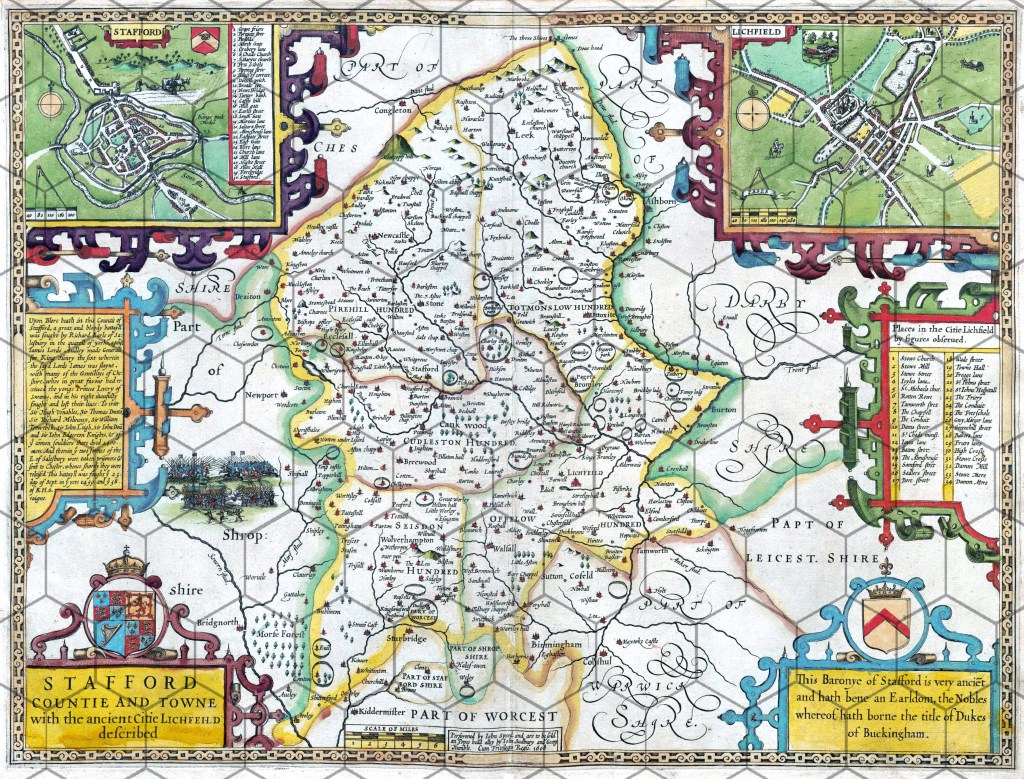

The best way to furnish a map is to start with a map of a real place and modify the coastline to be unrecognizable. Then you’ll know where mountain ranges, rivers, and major cities should be, all realistically laid out without much effort. Just remember that there should be large areas of untamed wilderness.

Humans migrating into an area would likely clear and cultivate areas near rivers, lakes, and coasts first, leaving large amounts of wilderness between, cut thru with trails, followed by roads. If there are monsters, it might be many centuries before they managed to tame much of the wilderness, and they would likely leave the worst of it (rocky wasteland, steep hills, and wetlands) to the fearsome creatures.

Populate the individual hexes with whatever terrain you want. You could even seam together two maps at similar terrain and still have a more realistic result than what you would get by making up your own. You can even change the scale somewhat.

Mountains & Rivers

Mountains usually act as borders and divide realms or noble lands within realms. Since they represent areas where two tectonic plates are colliding, they nearly always appear as ranges, or lines. There are usually highlands next to them and/or hills. But hills can appear virtually anywhere and can appear in very small numbers.

Rivers run from the mountains and other highlands to the sea. They don’t cross continents. Slow-moving rivers thru flatlands tend to be wide and meander and can double-back on themselves and/or create a marsh/swamp/fen/bog. Fast-moving rivers are narrower, straighter, and tumble over rapids and such. Either can have a waterfall of any size wherever the land drops.

Modern-day rivers are nearly all channelized and managed to reduce wetlands, so don’t go by your personal experience. Try to find pre-20th-century maps as models.

Settled Lands

Settled, cultivated lands generally consist of manors and fiefdoms and their attached villages, as well as yeomen’s lands. Historically, a manor or knight’s fiefdom tended to be 900 to 2000 acres, depending on the quality of the land, so they take up 1 to 3 square miles each. A yeoman’s land would be smaller–perhaps 200 to 400 acres, essentially run as a family farm (but usually with servants). Traveling a road in a settled area would take you thru several villages between two towns.

Each village would have, up a long lane, a manor house. This could be fairly grand, if the lord’s family lived there, or rather humble (just a hall and kitchen), if they lived on one of their other manors. It was managed by a bailiff and, if the lord lived elsewhere, a steward. The village was managed by a reeve and the village priest (altho a village too small to warrant a church was called a hamlet).

Since villages were not walled, during an attack, the villagers would run to the manor house and defend it from inside its walls or hide in the hall. On market day each week, many villagers take excess fruit, vegetables, eggs, and livestock (usually geese, ducks, or pigs) to the nearest town to sell them at market.

Towns & Cities

Cities grow up around resources, particularly water, lumber, and mines. The most important resource is water, because it can be used to move goods from place to place, creates a barrier from attack, is a source of fish, and–if freshwater–can be drunk. Any large lake or sea should be surrounded by settlements.

On a 6-mile hex map of a settled area, there should be a city every three or four hexes, connected by roads. Most should be on river, lake, or coast. Between them would be towns, but there would be too many to bother mapping, since they would appear every hex or two in settled lands.

Towns and cities are surrounded by manors, which feed them. Many of the townsfolk work on the nearby manors. Each county/shire/province should have a city, where there is a court of law and a noble’s court (and castle).

Roads connect towns and cities and do not meander unless they are avoiding something, like marshy ground, dangerous monsters, or steep hills. Bridges are expensive; roads bridge them at narrow points or ford them at shallow points.

Check out my list of 100 Fantasy World Towns & Cities for inspiration.

Other Points of Interest

Instead, add points of interest every six to eight hexes. My 100 Fantasy World Points of Interest post can help with numerous categories.

- Architectural Wonders

- Attractions

- Markets

- Lost Treasures (presumed locations)

- Natural Wonders

- Unnatural Wonders

- Lairs and Homelands

- Mysteries and Foreboding Places

- Pilgrimage Sites

Leave a comment