I wrote previously about the theoretically perfect game system. The perfect D&D-style fantasy RPG system would naturally be integrated with its own campaign world, but this world would be generic enough that it doesn’t introduce weird complications and elements that differ too much from traditional worlds (like Forgotten Realms or Golarion). Real weirdness should be left to the game master to add, and help should be provided to do so, such as evil overlords, secret cults, and fantasy factions.

Dolmenwood is a very impressive game system with an incredible, integrated campaign world, but the quirkiness of the setting makes it of limited use to anyone who doesn’t go for its particular brand of dark fairytale silliness. The Land of Eem is similarly impressive but even more cartoonish.

So the perfect campaign world should have much that’s right at home in any fantasy RPG world and a little that’s specific but optional or which is modular enough to leave out. It would be about 200 pages long–long enough to have rich material, but not so long that it’s expensive and hard to find what you’re looking for.

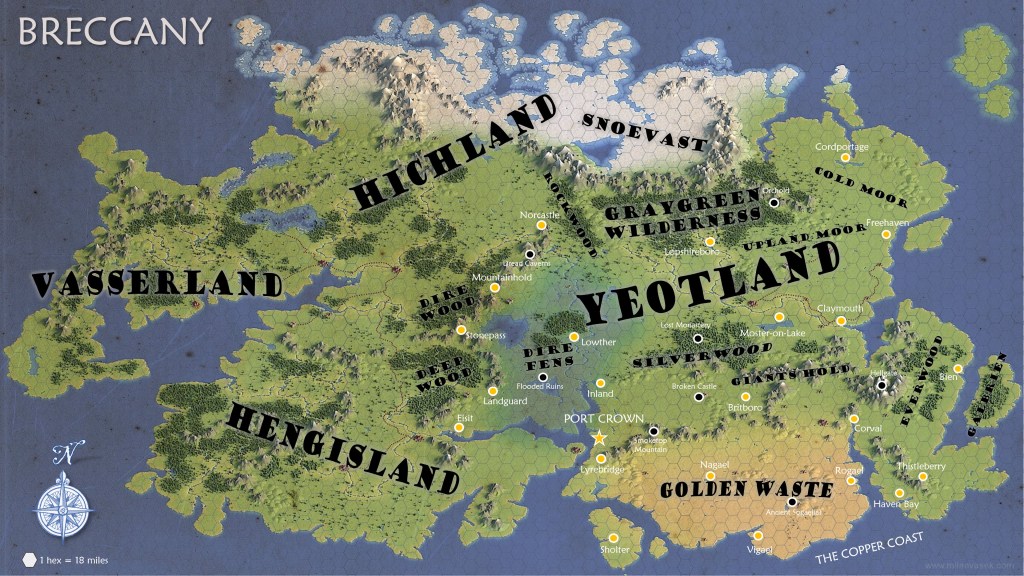

Realm Maps

There should be a nice, big map of the campaign world that covers perhaps four principal realms (kingdoms that share a culture). This should be a big piece of art suitable for the players to look at. Then, in the book, each quarter of the map should have an 18-mile hex map on one page with the facing page being an overview of the lands in those realms. Unlike the artsy player map, these maps should have specific terrain indicated for each hex.

With a few extra pages on history and religions, this section would require 12 pages. It might seem odd to offer a campaign book with such small attention to history and religion, but these are honestly two of the least important things in world-building. And including elaborate material on them would not only be a waste of pages but could turn off GMs who don’t like those specific choices.

The history should include something like a First Kingdom, an Old Empire, a period of rule by a Dark Overlord, a Second Kingdom devastated by a plague, and the new era of the Third Kingdom. Then GMs can say:

- These tombs date to the First Kingdom, during the Age of Iron

- This ruined Imperial fortress features fine mosaics and lingering magic.

- This temple dates to the Dark Overlord’s rule and may continue to harbor eldritch evil.

- This old monastery from the Second Kingdom was abandoned during the Great Plague.

- This elaborate lair was only recently excavated in secret.

All these have implications about architectural style, magic, condition, treasure, and such that further inform the GM in creating the adventure and inform the players in choosing the adventure.

Travel

Simple rules for travel on the realm map should need only one page. Since travel on the big map would typically be by road between cities, and those are 18-mile hexes of settled land, most large-scale travel is just a matter of saying the heroes travel 1 hex per day on foot, 2 hexes per day by horse.

Hex Maps

City Hexes

The realm maps should be followed by a section with small-scale, 1-mile hex maps that represent each of the 18-mile hexes that contain a major city on the large-scale maps; these maps would include the city, the nearby towns, and the known perils (ruins, caverns, etc.). The hex map would be in the top half of each page with a map of the city in the bottom half, and (as you can see at right), there’s enough room for some text to describe the maps.

The facing page would be a key for the various points of interest on the maps and information like the city’s major industry, with a focus on hooks that can draw the heroes into an adventure or political machinations. There would be perhaps eight of these for each realm, so 32 pages in all.

The city map should label the neighborhoods; then the text could just mention the neighborhood where the tavern or sage’s house is located, rather than tagging specific buildings. The neighborhood labels could even be coded (color and icon) to indicate what type of area it is: squalid, labor, craftsmen, rich, or public. A single set of encounter tables could then serve all towns and cities; some would have more crafts and rich neighborhoods while others would have more squalid and labor neighborhoods.

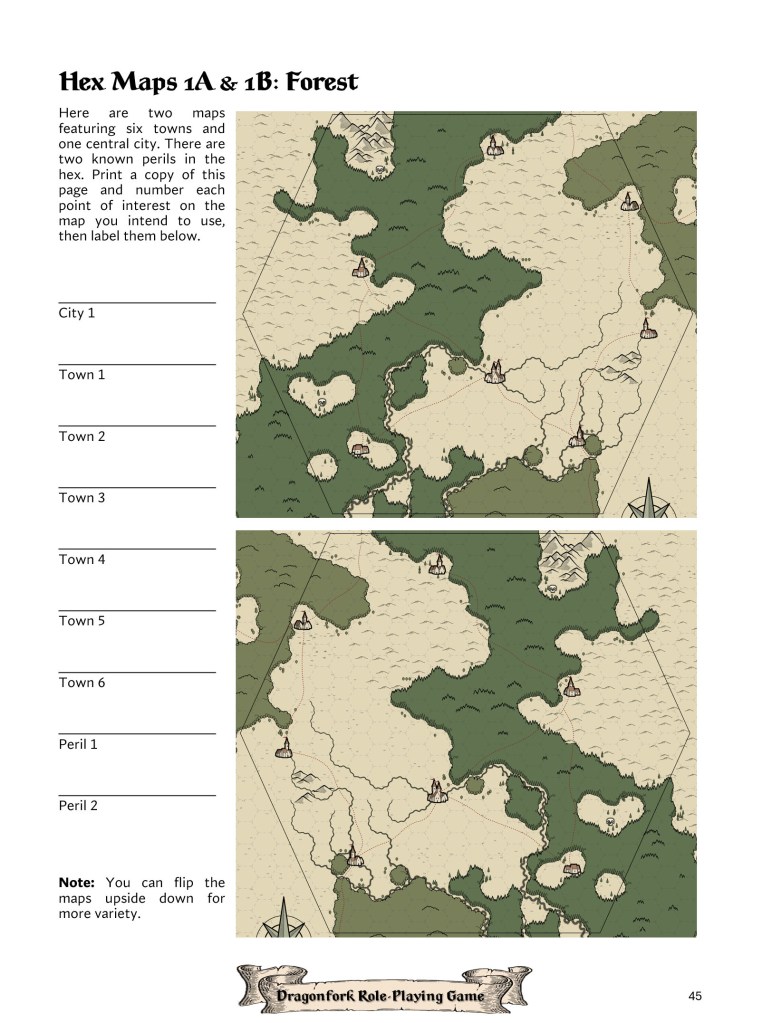

Generic Terrain Hexes

Next would be a section of maps of generic hexes for each terrain type. Each page would feature two hex maps. There would be four pages for each terrain, making 8 maps (32 if reversed and/or flipped). That’s 4 pages for each of 10 terrain types, so figure 40 pages for this section.

Coasts would follow the edges of hexes, so there would be no need for special hexes with coastlines.

Exploration

Simple rules for exploring (hex crawling) small maps should fit on one page, used when the heroes leave the main roads. On these maps, each time the heroes enter a hex, roll to see if they find anything of interest and if that thing is mundane (pond, druid’s cottage, abandoned ruins, uninhabited cave, etc.) or special (magical meadow, inhabited ruins, monster lair, etc.).

This section would be just two pages.

Points of Interest

The final section would list points of interest the GM can site on his or her copies of the maps or roll up as a result of travel, with a focus on adventure hooks. Each page would dedicate a half page to each major point of interest and a short paragraph (about 1/8th of a page) to each minor point of interest. So 100 major points and 200 minor points would fit on 75 pages.

This would include a small variety of maps of lairs, tombs, towers, camps, temples, manors, castles, cities, and a few unusual locations. There would be one large or two small maps on each page with locations labeled directly on the map, so no key is required. It’s up to the GM to add specific monsters, traps, puzzles, and other challenges (copy the map and use the generic key to create your own full-featured key). About 20 pages.

And finally, there would be a few pages about fantastical plants and creatures that aren’t monsters; that is, they’re mostly harmless.

About 100 pages for all this material. That brings the total page count to about 200 for the campaign world.

Cultures & Languages

The setting should have four or five major cultures/realms, and three or so should be viable locations to start adventuring from. It’s strange that so many fantasy RPGs embrace the idea that humans speak a common language but other intelligent creatures speak their own (species) language. The perfect fantasy setting would be a bit more realistic but still quite simple.

Humans of each of the major cultures would speak the language of their culture. Personally, I like the idea that one is a bit like Britain, one a bit like France, and one a bit like Italy if it maintained more links to its Roman Empire past. Minor cultures/realms would include one that’s a bit like Arabia with African animals, one that’s a bit like Scandinavia, and maybe one that’s a bit like German and Slavic lands. That gives us reason to have vaguely French and Italian names, for example, which is fun.

The elves would have their own minor kingdom, culture, and language, as would the dwarves. Halflings would straddle the world of humans and elves.

Intelligent monsters would generally speak “the black tongue”. I don’t really see a reason for have a draconic or infernal language. The great majority of players don’t want to have to hire a translator, after all, so most games do this weird thing where they pretend it makes sense that all the characters speak three or four languages, including those of monsters. If practically everyone can speak to practically everyone else, then why bother with different languages? I like the idea that instead of “thieves’ cant” (which I suspect hardly anyone uses), rogues–and only rogues–can speak the black tongue. That makes rogues more useful and interesting, I think, as they alone can negotiate with awful monsters.

I also like the idea that there’s an ancient or imperial language (like Greek or Latin) that the well-educated all speak, regardless of culture. So the wizard can converse with a foreign priest in Imperial, read magical writing, and so on. If a thief invests a skill on Imperial, he or she can sometimes read scrolls and cast their spells, altho it’s a bit risky.

Leave a comment